Chris Johns

Expect the (very) unexpected. Some unusual suspects: both the past and the future are not what they seem.

The world economy has sublimated: disinflation to inflation in a heartbeat. Growth might be slowing.

It turns out that China’s multi-decade growth miracle has very shaky foundations: a mega housing bubble. How they handle this bubble has implications for all of us. China is slowing and we may need to get used to China not growing very much at all.

Workers of the world are uniting and resigning

Is the energy shock going to derail the world economy? Has it already?

“The Bank of England is determined to repeat the ECB’s mistake of a decade ago: raise interest rates too soon and cause a double-dip recession.”

“Every central bank is repeating the policy mistakes of the 1970s and encouraging inflation. Disaster awaits”

Only one of the those last two points can be right. They could both be wrong

Economists, unlike epidemiologists, don’t trust their models. The new economics answers every possible question with ‘it all depends’

Economist (new) humility extends to inflation: we have no agreed universal theory about what causes prices to rise or fall. It really does all depend. That might cue a lot of economist jokes but, in reality, represents real intellectual improvement.

The chances of an economic policy mistake are high - that’s always true. But, all things considered, a big mistake is now more likely than not. Maybe more than one mistake.

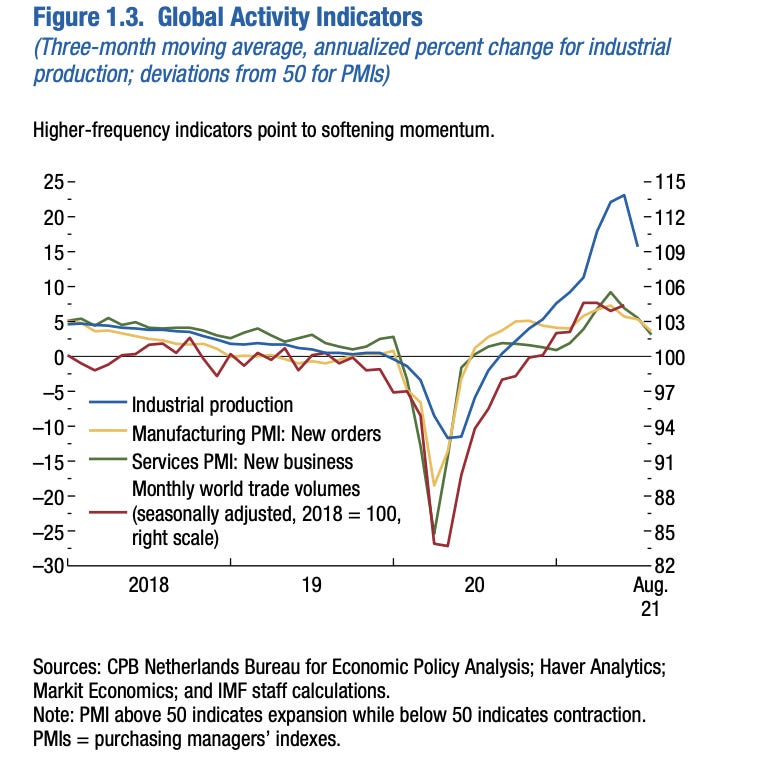

It looks like the world economy is slowing. But maybe only for a while. Nobody knows. From the IMF: look at the right hand side in particular.

A long time ago (about 6 weeks ago to be fair) I penned a piece (here) bemoaning the fact that even at the best of times we know precious little about the future of the economy (any economy). That these are not the best of times is obvious: post-pandemic (with hope attaching to that word, ‘post’), policymakers have no forward visibility and a murky rear-view mirror. Figuring our what economies have been doing over the past few weeks is unusually tricky; crystal ball gazing is harder than it has ever been.

Looking back to when the pandemic started, the forecasts made at that time, is evidence enough for the prosecution. Everyone has been humbled, sometimes greatly. From The Economist:

Does anyone really understand what is going on in the world economy? The pandemic has made plenty of observers look clueless. Few predicted $80 oil, let alone fleets of container ships waiting outside Californian and Chinese ports. As covid-19 let rip in 2020, forecasters overestimated how high unemployment would be by the end of the year. Today prices are rising faster than expected and nobody is sure if inflation and wages will spiral upward. For all their equations and theories, economists are often fumbling in the dark, with too little information to pick the policies that would maximise jobs and growth.

The pandemic has been responsible for much, but by no means all of this. The inadequacies of the economics profession are well known and won’t be rehearsed here. There are grounds for optimism: we take much more account of data these days, pure theory is no longer as dominant as it was in academe and we were already in a more humble state thanks to the prior, Great Financial, crisis.

The US economy drives the world economy. There, overall growth expectations have mysteriously collapsed over the past few weeks. But corporate investment spending is going through its strongest phase since the second world war. At the same time, inflation expectations have risen to multi-year highs.

If I had correctly foreseen the contents of that last paragraph I would have added: ‘bond yields, interest rates and the dollar will go up, equities will go down’. And would have been dead wrong about that stockmarket forecast. Another reminder about the perils of forecasting. At least I would have got something - rates - roughly right.

If economists now know how much we don’t know and admit the impossibility of forecasting, how do we do policy? ‘With great difficulty’ is the answer, with even more scope than usual for big errors. That well-known CEO of Twitter thinks he knows what is coming next:

He could be right, but is about as unlikely to be right as everyone else.

What we do know is that the global economy has become supply constrained after decades of everybody moaning about demand deficiency. What we don’t know is whether or not the supply-chain problems, so evident across many sectors, are permanent. Likewise their associated upward price pressures. To repeat: we simply don’t know.

We have theories and some evidence about the supply shortages but nothing conclusive. The shortages and inflation will prove temporary if economies are just starting up again at varying rates but quickly go back to where they were producing before. If things have shut down permanently and/or one or two large economies have been over-stimulated then we have a long-lasting problem.

Negative scarring and another big surprise

Economists fret over pandemic scarring: the effects of Covid will be, economically at least, permanent. Economies will, for a very long time, be smaller than they would otherwise have been. Unemployment will be permanently higher, government deficits harder to close.

But not, amazingly, in the US. Apparently.

A notable feature of the all-important US economy is that forecasters (that word again), notably the IMF, think the US economy will now be bigger as a result of the pandemic. Not because of Covid per se, but because of the extraordinary monetary and fiscal stimulus that accompanied it. The US authorities simply went bigger than every other policy maker around the world. Joe Biden embarked on a remarkable fiscal expansion, fully supported, with great alacrity, by the Federal Reserve. As a direct consequence of this most remarkable policy experiment (one that is not remarked upon enough). This, from the recently published IMF World Economic Outlook:

I sometimes wonder whether chart/graph drawers aim to impress us with their hyper-intelligence rather than informing or clarifying. This chart is, in fact, simple and clear: the US economy is expected to be a good bit larger because of the pandemic and to generate a lot more jobs than if the virus had never happened. That is, economically at least, truly astonishing. But the US can’t pull the rest of the world up with it, at least according to the IMF: scarring is long lasting everywhere apart from America.

A simple economist might look at this in isolation and conclude that the US might have an inflation/supply shortage problem as a result of this (recall that the US was at full employment going into the pandemic), but not anywhere else.

Workers revolt

That suspicion about US inflation is consistent with developments in the American labour market: wages are on the up.

Elsewhere, there is evidence, albeit patchy and anecdotal, that worker bargaining power is on the up for the first time in a generation

The well documented pan-European HGV driver shortage, particularly in the UK, has echoes in other sectors. Care home workers in Britain are in very short supply. Hospitality businesses report difficulty in attracting staff (and higher costs, not just for labour).

There is plenty of speculation about ‘The Great Resignation’, the decision by millions of workers, particularly in the US, that their jobs low paid and/or poor conditions, aren’t worth returning to. This, again, may or may not prove temporary.

The upshot of all this is that this author believes we have never lived in more uncertain times. Economists often say that. For once, it happens to be true. That’s just the economics. Trump’s comeback, the Monty Python sketch that is the state of British politics, Europe’s fascistic Eastern fringes, Putin’s gas-price politicking, Xi Jingping’s Taiwan threats, the environment, pandemic resurgence: let’s leave all that to future posts.

An optimistic spin

To avoid ending on too gloomy a note, it’s important to remind ourselves, again, about the perils of forecasting. There are lots of ways all of these concerns could turn out to be benign. All of that wage inflation in the US, for instance, may contain a silver lining: it could be the single biggest factor behind the failure of Trump’s attempt at re-election: one of the key drivers of populism, the fact that you have been left behind, could be about to be removed.

Wage inflation will - probably is - nudging firms to invest. Productivity growth may magically come back. We will all be better off as a result.

All of that extra US growth could spill over into innovation and, more generally, a burst of creativity. Perhaps even in other countries. If the world is suddenly short of workers, we may be spared, for a while, all those dreary articles about ‘the rise of the robots’.

Things could turn out ok. Boris Johnson might even become unpopular.

Unbelievable content there lads.Yourselves and Dunphy are doing some job.

The Other Hand is an excellent podcast as are the substack articles. I was struck by Chris' comments to Duncan Weldon about how this is now the preferred forum for commentators - free from the shackles of newspaper editors and the frustratingly dumbed down mainstream radio/TV. The big problem though is finding out that these podcasts exist in the first place. I wouldn't have known about this one had it not been for Eamonn Dunphy's podcast, which again I only stumbled on by chance.

Another problem is for how long will Chris/Jim be prepared to do all this work for free - other podcasters (e.g. David McWilliams) are starting to charge fairly punchily for their subscriptions which has to be the way to go given the presumed difficulties of attracting advertisers to 'niche' podcasts as this one.

But very grateful all the same for one of the best serious discussions of finance and economics out there.