Gradually then suddenly: the UK's problems

The list is getting longer and deeper. And is crossing the Atlantic.

Some time ago I wrote a series of posts outlining just how deep-seated are the UK’s problems. The first was:

and the last (to be honest, not really the last, I’ve been banging on about it ever since):

Those posts were written so long ago it is scarcely believable that they still seem so relevant - if anything, they barely scratched the surface of the problems. Writing posts like those used to be a bit of a cottage industry; now, everybody is at it. But don’t let familiarity become contempt. Some recent efforts are really worth reading.

Leading the pack is a superb, long essay by Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes and Sam Bowman here. It’s attracted a lot of attention amongst policy wonks and deserves mass readership. It lists what has gone wrong:

France and the UK have similar populations. France has 7 million more homes than the UK

The UK generates 2/3 of the electricity generated by France and ‘barely’ over a 1/3, on a per capita basis, than the US

Infrastructure building costs in the UK are ridiculous. Tram projects are 2 1/2 times higher than in France. Each mile of the (now partly cancelled) HS2 railway will cost more than four times more than a similar line built in Italy. (Italy!)

Since 1980, France has built 1,740 miles of high speed rail; the UK has built 67 miles. France has 12,000 km of motorway; Britain has 4,000. Over the past quarter century France has built more motorways than currently exists in the entire UK motorway system. The UK has seen its railway lines shrink by 50% over the past century.

Crossrail, the truly magnificent Elizabeth line, has been a massively beneficial addition to London, despite its cost. The Paddington to Stratford section, for instance, cost £1.4 billion per mile. Madrid built its own metro at a cost of £68 million per mile. Ironically perhaps, the reason why cities call their transport systems ‘Metros’ is that the first such railway was the Metropolitan Line, built in the 19th century when the UK knew how to do such things.

Newt, bat and other environmental assessments cost a fortune and stop development. The environmental impact assessment for 3 miles of proposed railway track linking Bristol with Portishead ran to 18,000 pages and cost £32 million. The similar documents for London’s Victoria Line, built over three decades ago, ran to 400 pages.

Despite a population 10 million higher than 30 years ago, not a single reservoir has been built in the UK during that time.

Heathrow’s flight numbers have been flat since the beginning of the century, notwithstanding rapidly increasing demand.

The NHS has the fewest MRI and CT scanners of any developed country’s healthcare system.

Apartment blocks with one staircase and one lift core (the standard in almost every other developed economy in the world) are now banned in the UK. The government’s own analysis of this rule found the costs outweighed the benefits by more than 200 times.

It is now very hard to build houses with windows as large as those constructed in Victorian and Georgian times. I have always thought this was because builders found it cheaper to deprive homes of much-needed light. It turns out that some flunky decided that large windows cause homes to overheat in the Summer. Presumably, this rule was written by someone working from home - somewhere on the Riviera. The bureaucrat was also worried about people falling out of larger windows.

The price of a British house is roughly double its building cost. In the US, homes are priced at a third over their construction costs.

There has long been a need for new river crossings of the Thames. None get built. The planning documents for the Lower Thames Crossing runs to 360,000 pages. That planning process - just the application, not the construction - has cost £297 million. Norway has managed to build (not just plan) the longest tunnel in the world for less than half that.

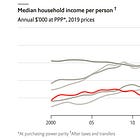

Median annual real wages for full-time workers are 6.9% lower than in 2008

I could go on - the authors of the report certainly do. Some or all of these problems will resonate with readers in the US and Ireland, if not elsewhere. Southwood et al go into great detail about the legal and institutional obstacles to building pretty much anything in the UK. The reader is left wondering how anything gets built at all. It’s not just about NIMBYism but there is certainly a lot of it about.

Southwood et al pin a lot of the blame on the planning restrictions introduced after the Second World War and the steady creep of the regulatory burden ever since. It’s also a story about ever shrinking state capacity.

Noah Smith, on his Substack, describes the UK’s experiences of the past few decades as an explicit experiment in degrowth: the agenda favoured by some environmentalists. “We can only save the planet if we at least stop economic growth, if not start to shrink our economies”. Mainstream economists, like me, have longed looked at these kind of suggestions with horror (and mocking). If you think the world has problems with climate, just wait until you see what a few decades of degrowth will do.

The more I think about Smith’s remarks, the more I realise that he is absolutely right: the UK has explicitly chosen degrowth. Whether or not you agree with all of Southwood’s conclusions, it’s impossible to disagree with the basic point: the UK has chosen to ban (or make difficult/costly) building anything. Smith also notes that the US shares many of the UK’s dysfunctions:

But the UK also has various other problems that the U.S. generally doesn’t have, such as hard government limits on urban sprawl combined with height restrictions that prevent density. America and Britain both make growth very hard; Britain often simply forbids it…The result of all these British policies is real, actual degrowth — not the neo-pastoralist fantasies of faux-environmentalist postdocs, but concrete policies designed to placate the citizenry by preserving the built environment of the recent past. Real degrowth isn’t a yearning for the 1700s, but for the 1970s. Change is scary, and ensuring people that the government will prevent change is what I call a “stasis subsidy” — a promise that looks cheap in the present because it incurs no fiscal costs, but creates huge economic costs down the road. The UK is paying those costs now.

There is much to ponder - and agree with - in the Southwood et al essay. One thing it fails to do is acknowledge that the causes of economic growth are imperfectly understood - at least from the perspective of policies aimed at promoting growth. Yes, the UK forbids building anything and it is almost certainly the case that if we lifted the restrictions we would, indeed, grow again. But this is not guaranteed. Those British people who don’t like economic growth (most people over 50 for instance) might well find new ways to remain culturally complacent. Officialdom might find new ways to waste investment capital if given to freedom to spend. But these are minor quibbles. The substantive point is that if we don’t find a way to lift the rules forbidding building anything, we will not build anything.

It’s also true that Southwood et al don’t mention other reasons for the UK’s degrowth. It might not just be all about capital investment. Britain is now sicker than its global counterparts. Indeed, the current generation of Britons could end up sicker than their parents - something that is most definitely not supposed to happen. Thanks to ill-health, almost 1 million people have gone missing from the workforce over the past few years.

Britain’s politics haven’t been of any help for the economy - and don’t look like doing so. After 14 years of rule by over-educated faux-aristos, the UK now has a government led by people who are undoubtedly nicer than their predecessors but with similar skill-sets to those possessed by Rishi Sunak. In other words, the people running the country really belong in the middle manager ranks of Morrisons. Keir Starmer just looks as bewildered as any supermarket manager would be if he had suddenly been made Prime Minister.

Perhaps the biggest disappointment about the new Labour government is the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The manifesto promise was, absolutely correctly, all about the imperative of economic growth. Rachel Reeves, aided and abetted by Starmer, has utterly changed the narrative: she says that Labour is now focussed on the return of fiscal austerity. No doubt this will change (possibly via Starmer’s first cabinet reshuffle). But not before much damage is done. Already has been done.

Who could imagined this story, from Bloomberg, so soon after Labour’s victory, one that promised a new growth agenda for Britain:

Since Labour’s landslide July 4 election victory, Reeves has axed road and rail projects, put on ice a hospital building program, and told departments to find £3.2 billion ($4.2 billion) of savings this year.

Departments have come back with proposals to scrap an £800 million supercomputer and drop a £500 million artificial intelligence plan. Flood defences are under scrutiny. Electrification of the Trans-Pennine railway is in jeopardy and the National Health Service has been told it will not get the £37 billion needed until it reforms. Senior civil servants say privately they can’t cut further into the bone.

There are lessons for any economy in all of this. The biggest one of all: DON’T.

Perhaps there is an optimistic spin on all of this. The fact that everyone is now writing articles like this raises the possibility that someone will notice. You have to identify the problem before you can solve it.

Italian intercity trains are superb, btw.

I haven't read the Foundations essay but I have read Ed West's post about it and have to say that this displayed a poor understanding of Britain’s economic history. Its decline as an economic behemoth did not – as the post contended – start after WW2 (although it did accelerate then). It started way back in the late 19th c. – as soon in fact as better adapted nations (particularly USA, Germany and Japan) started to compete with it. The reasons are complex but none of the principal ones were flagged in that post. Principal reasons included: 1) the peculiar resilience of the British class system meant that manufacturing enterprise (‘trade’) was always looked down on and the 2nd generation of its great manufacturing dynasties got out of it as soon as possible. Hence Britain became a place brimful of lawyers and ‘what we would now call ‘creative & media people’ but woefully lacking in technologists and nuts and bolts engineers. 2) The Empire masked (and partly caused) Britain’s uncompetitiveness for many decades because it had a captive market for its lack-lustre products. https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/thinkpieces/the-consequences-of-economic-ignorance

Also crude economic comparisons between nations can be hugely misleading. For instance:

* Norway is a huge landmass with a low density population….easy to build infrastructure there. The Lower Thames Crossing on the other hand is in one of the most densely populated (and politically quarrelsome places on earth. Chalk and cheese.

* France is a big (and mostly low density) landmass and is administed by a powerful centralised elite civil service with powers, when it chooses, to override local opposition. Britain's administative culture is the opposite of this. Again chalk and cheese.